Ecodesign is for other people

Concerns about the environmental and societal impacts of digital technology are increasingly present. In particular, the impacts of websites are questioned. It therefore seems logical that we come across more and more sites advertised as eco-designed.

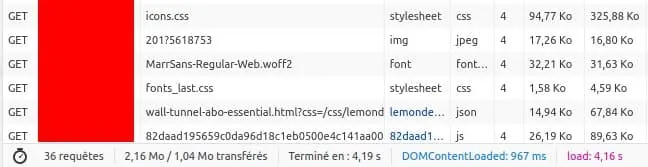

Recently, a French online press website claimed to have reduced its digital footprint. The good old reflex is to open the Network tab of the developer tools of your favorite browser.

36 requests, around 1 MB transferred… it could be worse but it’s not that good either. In any case, still better than what we can see on most online press websites (see the study carried out by Greenspector on this subject).

Except it doesn’t stop there!

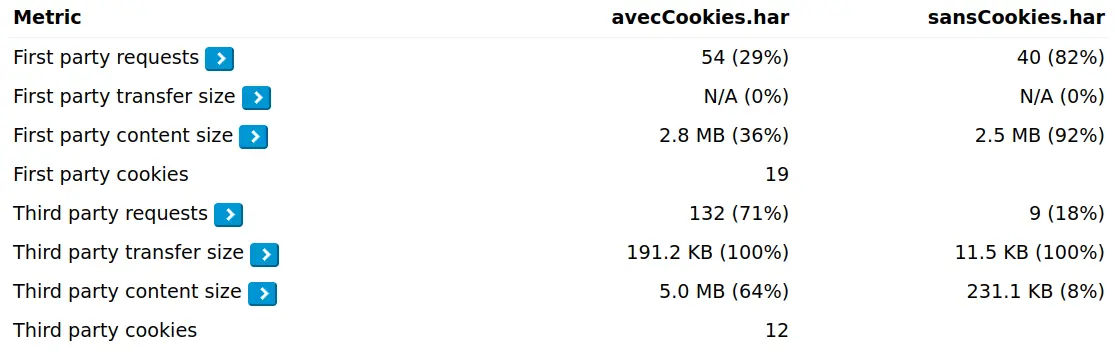

Naive, you may have visited this site to read the news. You will then need to check the consent window for cookies. If we assume that you accept them all (again in the purpose of accessing the news), you see that something is happening with the requests. Even more requests (especially from third-party services) and data transferred. This is what we see in the following table. If the number of first-party requests (those linked to the site itself) increases slightly, the number of third-party requests (from other sites) is multiplied by more than ten, as is the volume of data transferred.

Let us observe a minute of silence for web page “measurement” tools that do not validate cookies and thus miss the point.

But let’s go back.

A short history of web ecodesign

Intermission

If you have just discovered the environmental impacts of digital technology or web sustainability, here are some resources to help you go further:

- Environmental footprint of global digital

- MOOC from INR (Institute for Responsible Digital)

- MOOC from INRIA (National Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation)

Back to the 2000s

During the 2000s, awareness of the environmental impacts of digital technology grew, particularly in France. Attention then focused mainly on the web. Public tools were created to raise awareness (EcoIndex, EcoMeter, etc.) as well as repositories of best practices (the 115 best practices of the GreenIT collective).

It was a good start, but it was not enough. It was still mostly focused on optimization with a truncated vision of the impacts of a digital service. The approach was also restricted to the notion of website, or even web page.

So we were talking about the 2000s but where are we today?

The 115 good practices of the GreenIT collective (FR) are still there (fourth edition) and have been joined by other standards:

- GR491 (Reference guide for responsible design of digital services) from the INR

- The WSG (Web Sustainability Guidelines) proposed by the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium)

- The RGESN (FR) (General Framework for the Ecodesign of Digital Services), set to become the reference for the adoption of the ecodesign of digital services in public structures in 2024.

On this last point, it should be noted that the legislative context is moving forward (see the article on the Greenspector blog on this subject or the article on Apolitical).

Measurement tools for web pages are multiplying. Outside of the web, they immediately become much rarer.

And we still tend to offer courses based on knowledge rather than skills.

Not to mention the large companies which are multiplying their promises with “Net zero”, “carbon neutrality” or even “carbon negativity”. And the tools that offer you the opportunity to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of your code using artificial intelligence. In short, everything is going well.

Or not.

When ecodesign goes wrong

Here are some things to keep in mind before considering ecodesign:

- If you are looking to eco-design a digital service already in production, you are doing it too late. It’s like with bugs: the sooner it’s caught, the less costly it will be. Not to mention that this is not necessarily the ideal time to review the design or question user needs. In short, it’s too late. And dynamically managing the allocation of computing power according to the energy mix will not solve the problem (you will perhaps reduce greenhouse gas emissions but not necessarily water consumption, not to mention sovereignty concerns ).

- If you focus on loading a few pages of a site without taking into account the cache or cookies, you are missing the point.

- If you only collect transferred data, the number of HTTP requests and the size of the DOM (Document Object Model), you do not have a complete vision of the impact of the page (or user journey) on the user terminal. Missed again.

- If you only have one environmental indicator, you risk impact transfers in addition to missing out on a great opportunity to raise awareness on the various impacts of digital technology. Think criticality of mineral resources (FR) and water stress (FR).

Finally, a small list of what not to do:

- Optimize unused features

- Produce a lightweight site but without taking into account editorial sobriety

- Use oversized/over-engineered development tools and libraries

- Ecodesign a digital service whose purpose is ecocidal

- Optimize an unusable digital service (in the sense of digital accessibility)

Are you wondering if you are doing the eco-design of digital services appropriately?

Here is a little online quiz to approach the question differently.

Now let’s go over the basics to make sure we’re talking about the same thing.

Definitions

The different definitions available can be summarized as follows:

- Digital service = set of human, software and material resources necessary to provide a service.

- Ecodesign = approach to integrating the reduction of environmental impacts while designing a digital service with a global vision over the entire life cycle, through continuous improvement.

We generally distinguish 4 levels of ecodesign and we see that most optimization efforts are only part of the first level :

- Level 1 : basic technical optimization (minifying code, optimizing images)

- Level 2 : modifying some code dependencies or the whole stack

- Level 3 : rethinking how we offer the same service (an email rather than an online dashboard, a SMS rather than a mobile application)

- Level 4 : revisiting the culture from the enterprise or the business model (offering a service rather than a product)

In short, we restrict ourselves to product innovation when it is the (economic for instance) system that should be changed. I plan on getting back to this notion of ecodesign levels in another article.

The ecodesign approach requires involving everyone, during all stages of the project (and as early as possible).

OK but how ? Let’s start by looking at two approaches that are sometimes opposed: management by measurements or management by good practices.

Enabling ecodesign

First of all, there are several good reasons to measure:

- Comparison over time

- Monitoring degradations and improvements

- Comparison with others (digital services from the same entity or similar digital services)

- Reliable projections

- Assessment of environmental impacts

We still need to know what we are measuring:

- What dynamic? Pages, user journeys, components…

- What metrics? CPU, data transferred, energy, requests…

This implies defining an environmental budget with two possible approaches: thresholds not to be exceeded (not to degrade the impacts too much) or (preferably) targets as part of the continuous improvement process.

The measurements can help you to decide on certain technical choices upstream but also to evaluate the gains (or degradations) following the decommissioning of a functionality or the implementation of a best practice.

Finally, if measurements are an essential tool for continuous improvement, best practices are valuable for improving.

For this, we mainly distinguish the GR491 (very comprehensive and transversal) and especially the RGESN (which covers the entire life cycle of the project with a very practice-oriented approach). With the evolution of the legislative context planned for public structures in 2024, it is a safe bet that the RGESN will soon come to the forefront.

Thus, measures and good practices are inseparable.

Limits of the ecodesign approach

We therefore saw that a true ecodesign approach requires going very far and questioning many things. This is obviously not simple.

We must already keep in mind that we are here on a process of continuous improvement: everything will not be perfect overnight but we will have to seek to always do better.

In addition, the ecodesign approach can sometimes be criticized for relying on purely declarative elements (“yes, we did user research and optimized the code”). Some communicate only on the final result and in a rather vague manner (“my product is eco-designed or the result of an eco-design approach”, “my product has reduced environmental impacts”, etc.).

From a french perspective, one of the keys here is the RGESN. In addition to providing recommendations for the entire life cycle of the project, the new version of the framework imposes elements of proof which often go beyond the declarative. These elements help to structure the approach by imposing deliverables which will question the choices made during the project. Ideally, the audit based on the RGESN therefore gives rise to an ecodesign declaration but also to elements of evidence as well as a multi-annual improvement plan.

In an international perspective, this is the role we can expect from the WSG. They are still only guidelines and a draft (BTW, now is the best moment to contribute, try it out and provide feedback). Hopefully, this will result in worldwide sustainability standards that will help define local legal contexts to making websites more sustainable. One of the main drawbacks is that other digital services (such as mobile applications, software, IoT, etc) still (to my knowledge) miss such guidelines. And maybe a global structure to define and spread such guidelines and standards.

To return to the ecodesign levels (see above), sticking to level 1 is not really ecodesign because everything can very well rest solely on the development team. You must therefore go beyond (ideally up to level 4) and be able to prove it. Gathering this evidence and reporting on how the process is carried out makes it easier to communicate. In this way, we limit the risks of greenwashing and raise broader awareness of the ecodesign approach by “playing down” the subject and sometimes opening up new avenues for reflection.

Conclusion

The eco-design of digital services is not an easy journey, but its application to websites is increasingly better documented. Until the measurement tools have managed to agree on indicators and methodologies, they can still be used with a view to continuous improvement. The RGESN and WSG will help you structure your approach and then explore further the topics that speak to you the most, for example Sustainable UX, code optimization, hosting, editorial sobriety and others.

However, don’t forget to take sustainability into account as a whole. Thus, we add to the environmental aspects societal aspects such as accessibility, privacy, inclusion, security, the attention economy and ethics. Keep in mind that ecodesign without social justice amounts to greenwashing.

And start by asking yourself if it is indeed necessary to digitize a service.